First Pages

Edit Your Opening for Maximum Impact

Hello, friends~

You only get one chance to make a first impression. By its very nature, the first page of your novel makes that first impression on potential readers. It must do the heavy lifting of capturing a reader’s attention, pulling them into the story, and kindling sufficient curiosity to keep them turning pages.

No pressure.

But the good news is, as writers, you are in control of when your manuscript ventures into the world, and we’re here today to discuss how to polish your first page so it makes an impact.

Before we begin, I would like to note that this advice works best if you have a completed draft and are going back to revise, whether it’s for a second draft or a fifth. While you should keep some of the details in mind while writing your initial draft, particularly if you plan or outline extensively ahead, most of it is much easier to apply and work out later, once you’ve a complete story and know how all of the arcs play out. Also, this is a hefty topic, and so I’m going to be breaking it down across a few posts. Okay, moving on.

Where to Start

Have you started your book in the right place? If you were to drop the narrative onto the timeline of your protagonist’s life, with everything that happens before page one lined up to the left of the book and whatever takes place after the end of the story (assuming your protagonist lives) lined up to the right of the book, have you sliced out the correct chunk of the timeline to include as your story? Should things start a little earlier? Or, more likely, a little later? If you’re tempted to tell your reader that things “get interesting” in chapter three, chances are good you should start there, or at least much closer to that interesting point.

This is often a second-draft problem, where you realize the first few pages of the story were simply you figuring out the characters and point of view and voice. They served as a warm-up for the action, which actually starts somewhere on page five or ten or twenty. Sometimes those early pages get bogged down with backstory or description and contain only the smallest amount of forward-moving activity.

Do not feel bad or beat yourself up if this turns out to be the case with your manuscript. It happens all the time, and not only with first novels. Just make note of what information you need to keep and cut the rest. As you revise the complete manuscript, you will find places to add the details you wish to retain.

Now that you are certain you’ve started the book in the right place, let’s look at that first page. Your goal, of course, is to hook your reader and to keep them turning pages. This starts with the first sentence. A first sentence should convince the reader to continue through the first paragraph, then first page, and so on. You want to layer in a lot of details and information, but it’s a balancing act, like walking a tightrope. Load your tightrope walker up with all the necessary bits and pieces—conflict, motivation, and so on—but you have to be careful. Too big a load and they will be weighed down and lose all forward momentum. Too much of any one thing and they will be set off kilter and lose their balance, falling off the tightrope entirely.

The Big Picture

Much like a journalist writing a lede, you want to front-load your opening with key elements that provide answers to the reader’s most basic questions about your story: Who, What, When, Where, and Why. How you do this, and also which of these receive more focus, will depend on your genre, but most of this information should appear on your first page if not the first paragraph or sentence. Use specifics from the start.

Who is the character who leads the reader into the narrative? Typically, this will be your protagonist, or sometimes the antagonist, depending how you choose to structure your story. It’s fine to start in medias res, but you need some establishing information about the character’s life so the reader has context.

Beware the temptation to explain the character to your reader. This leads to information dumps and sometimes blocks of backstory. Allow the reader to get to know the character through their actions and reactions. FYI: a first-person character telling the reader all about themselves is still an info dump.

When/where is the setting and time period, but also when and where are we within the story? Whenever you start the story is the time/date it starts. Don’t label your opening “ten years before” because we have no context for when “now” is in order to judge when ten years earlier might be. Unless using a stylistic opening related to time—Once upon a time, It all started with, etc.—set the opening scene as the present, whatever date that is, and then you can always time-jump the ten years in the next chapter.

For historical novels, establish the period and include some detail that grounds the reader in that time and place. For fantasy or science fiction, again, set up the groundwork for what readers should expect going forward. And if this is a magical world, whether fantastical or grounded, hint at that or outright establish it as soon as possible. But even real-world, contemporary stories need a sense of place. Do not ignore where your characters are in the physical world just because it’s ordinary.

Again, be careful not to include too much out-and-out description. Blend your setting into the action by showing us what the characters see, interact with, and experience in their world.

What asks both what is happening in the moment and what larger conflict is brewing. You need to establish conflict as fast as possible, which can either be the overall conflict for the story or a smaller conflict that gets the ball rolling and leads the character to the bigger conflict eventually. Keep in mind that conflict can be internal or external, and you will want to include both to start building tension and provide an emotional hook for the reader. This leads to why.

Why answers the reader’s question of why they should care and why they should keep reading, but also why all of this—meaning the action of the book—is happening. It involves character motivation, conflict, and some sort of emotional hook. Make the reader care about the protagonist, or conversely, make the reader care about something because the protagonist cares about it passionately. But you also want to include your overall conflict, the why of your story, as soon as possible. It might be readily identifiable, or it might be something that becomes clear when a reader looks back later and says, “Oh! That was the problem from the very beginning!”

How you decide to include these details, and which you prioritize, will develop naturally based on genre. More literary and/or character-driven novels will feature more character development, while SFF might include more world-building, and a thriller more heightened conflict. But readers expect to learn all of these basic details in the early paragraphs of a novel, so they can determine if they want to keep reading.

Prompting Questions

To pull a reader in, to involve them in the action of the story, you need to provide action. I do not mean there needs to be a battle on page one, but something has to happen quickly, and that action needs to continue to build both forward momentum and tension. You also do this by offering up specific information and details that prompt the reader to ask their own questions of the narrative, questions they will read on to answer. You want the reader to ask: What will happen next? Who is this strange hero/heroine? How can they get away with this behavior? What is life like in this world? And so on.

Does the first page of your manuscript invite the reader to ask anything? Have you set up a small conflict that leads to a larger, more complicated one? Or is the major conflict of the novel already evident?

A good way to see how this can work is to read the first pages of favorite books within your genre and note both what information you learn in the first paragraph/page/chapter, and what questions you would ask if you were coming to the novel with fresh eyes.

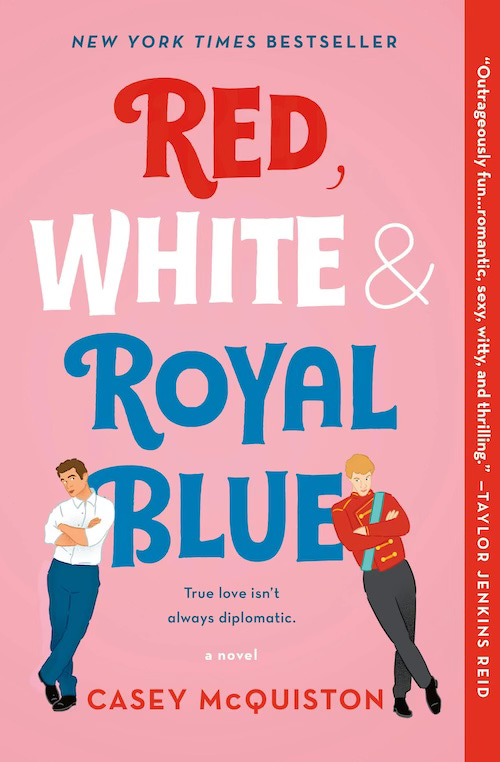

As an example, let’s take a look at the first few paragraphs of Casey McQuiston’s Red, White, and Royal Blue:

On the White House roof, tucked into a corner of the Promenade, there’s a bit of loose paneling right on the edge of the Solarium. If you tap it just right, you can peel it back enough to find a message etched underneath, with the tip of a key or maybe a stolen West Wing letter opener.

In the secret history of First Families—an insular gossip mill sworn to absolute discretion about most things on pain of death—there’s no definite answer for who wrote it. The one thing people seem certain of is that only a presidential son or daughter would have been daring enough to deface the White House. Some swear it was Jack Ford, with his Hendrix records and split-level room attached to the roof for late-night smoke breaks. Others say it was a young Luci Johnson, thick ribbon in her hair. But it doesn’t matter. The writing stays, a private mantra for those resourceful enough to find it.

Alex discovered it within his first week of living there. He’s never told anyone how.

It says:

RULE #1: DON’T GET CAUGHT1

This opening gives us some basic, grounding information right from the start. We know the story takes place in the White House and features Alex, who is the son of the president, so we’ll be privy to lots of inside information and secrets. There’s a bit of levity or mischief, since the secrets mentioned aren’t scandalous. And, given the prominent placement of Rule #1, it’s a pretty good bet he’s going to do something secretive of his own and get caught doing it.

At the same time, we as readers are prompted to ask a number of follow up questions. How old is Alex and what trouble is he going to get into? We can guess the story is pretty modern, given the presidential children mentioned, but is it actually contemporary? Who is Alex’s presidential parent? Who is part of this secretive gossip mill? What other secrets do they have? Can they actually be trusted? What was Alex doing on the roof of the White House a mere week after moving in?

The back-cover blurb provides some of these details, but there are still plenty of questions to keep someone reading. Anyone familiar with the story knows that, by the close of the first chapter, we have a solid voice established with a cast of characters that embraces classic rom-com banter, a few obvious romance tropes in progress, and layers of conflict that set up both the short- and the long-term action of the novel.

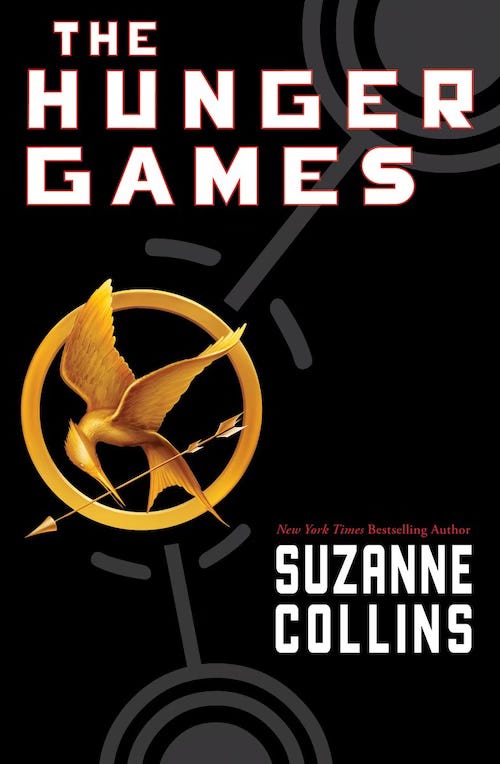

In contrast, read the opening to Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games:

When I wake up, the other side of the bed is cold. My fingers stretch out, seeking Prim’s warmth but finding only the rough canvas cover of the mattress. She must have had bad dreams and climbed in with our mother. Of course, she did. This is the day of the reaping.

I prop myself up on one elbow. There’s enough light in the bedroom to see them. My little sister, Prim, curled up on her side, cocooned in my mother’s body, their cheeks pressed together. In sleep, my mother looks younger, still worn, but not so beaten-down. Prim’s face is as fresh as a raindrop, as lovely as the primrose for which she was named. My mother was very beautiful once, too. Or so they tell me.

Sitting at Prim’s knees, guarding her, is the world’s ugliest cat. Mashed-in nose, half of one ear missing, eyes the color of rotting squash. Prim named him Buttercup, insisting that his muddy yellow color matched the bright flower. He hates me. Or at least distrusts me. Even though it was years ago, I think he still remembers how I tried to drown him in a bucket when Prim brought him home. Scrawny kitten, belly swollen with worms, crawling with fleas. The last thing I needed was another mouth to feed. But Prim begged so hard, cried even, I had to let him stay. It turned out okay. My mother got rid of the vermin, and he’s a born mouser. Even catches the occasional rat. Sometimes, when I clean a kill, I feed Buttercup the entrails. He has stopped hissing at me.2

This opening has a more serious, if equally confiding tone. It’s first person, so we don’t immediately have an identity for the speaker—though we learn soon enough it’s Katniss Everdeen—but we have plenty of subtle world-building. Something sinister is on the horizon, something that causes Prim to have nightmares and climb in with their mother, and we have the first mention of the mysterious reaping.

We can assume our speaker is an older sister, as a brother would probably not start the night sharing a bed with his sister. There’s a sense of poverty and hardship, with talk of mouths to feed and the mother’s worn looks, and we can already determine Katniss is the family provider and possibly protector as well, and has an obvious soft spot for her sister. She also comes across as strong and willing to make difficult choices, evidenced by her story of trying to drown the cat.

A reader’s first questions will probably include: What is the reaping? Where is this taking place? Does this family have a father, and if not, what happened to him? Why is this girl carrying such responsibility on her shoulders?

Reading further, one gets some of those answers very quickly. We have the first mention of District 12 and the sorts of people who live there, Katniss’s description of going hunting and the laws she breaks as a result, memories of her father, and more about the reaping. But we also start to meet the other characters who play significant roles in Katniss’s life, and get a sense of the status quo that is about to change. By the close of the chapter, we have an expectation of what is going to happen during the reaping, but Collins throws that expectation out the window with the actual result. Readers turn the page to chapter two because they need to learn how Katniss will react.

Katniss herself is not a likeable character, but readers admire her fierceness, her responsibility, and how she cares for her sister. Someone who loves that way cannot be a bad character, despite her cranky demeanor, and so readers follow her and root for her because they know what it is like to want to protect someone they care about. They can relate to her terrible choice.

Considering Your Own First Pages

Read through your first page and on through your first chapter, and ask yourself how a reader will be pulled into your story. Are you tugging on their heart strings, building a sense of empathy, or lighting a burning curiosity to see what happens next? Have you woven unique details into your opening that have a reader wondering what you mean? Intrigued by your character? Or looking forward to some good insider information? Is there some sort of action to pull the story forward?

I’ve covered a lot of ground here, and so I recommend you consider these different aspects of your story one at a time, noting which things work well in your opening chapter and which ones need revisiting. Don’t start to revise until you have the full picture of what you want to tackle, because some of these details will overlap each other or cancel each other out, and you’ll find you need to make some choices. For instance, not everything needs to make an appearance in your first sentence, so take time to think through what will have the most impact, given your genre, your conflict, your characters, and what sorts of expectations your readers might bring to the story.

The start of a book serves as an introduction to all the aspects of your story: the characters and setting, the conflicts and emotions. But it also invites your readers along for the ride. You want your readers to dive into the book in order to get answers to their own questions, to follow the trail of breadcrumbs you’ve sprinkled through the text. The situations you set up at the start of the book will eventually lead to the resolutions at its close, and it’s through closing those loops that you provide your reader with a satisfying conclusion.

I hope this serves as a jumping off point as you edit your first pages and build your own impactful openings. In a later post, I will circle back and discuss some of the less straightforward strategies for opening pages, and how those techniques can help (or sometimes hinder) the process of hooking your reader. But in the next installment of this series, I’ll be drilling down to first sentences and discussing ways to write a memorable opening line and set your first page up for success. Look for it in coming weeks.

Meanwhile, wishing you some wonderful writing time, plus a terrific read or two stacked on your nightstand. Don’t forget to see what makes those first pages sing! Until next time. 🥰

Red, White, and Royal Blue by Casey McQuiston, St. Martin’s Griffin, New York, NY 2019; chapter 1.

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, Scholastic Press, New York, NY 2008; chapter 1.

Yep! While my opening to Graveyard Girls was meant to align with Georgie's death in IT, I realized that the victim zero opening is fairly common in horror. And we also saw that in George RR Martin's opening in A Game of Thrones.

I do remember a handful of romances that open in another POV than the hero and heroine, and I think they were all done by Judith McNaught, who defied the rules in other ways too, by covering the heroine's backstory and growth and not having her meet the hero until 1/3rd of the way in. But for me as a reader and a writer, those without McNaught's magic had me writhing with impatience for the characters to meet. And me getting paranoid in my own drafts about taking too long.

My first publisher was insistent on always introducing the heroine first...which I found sometimes doesn't work as well and I STILL wish I could have kept my opening One Bite Per Night with the hero's POV because he set up the premise and conflict so perfectly.

So by the time I got to writing the Hearts of Metal books for my 2nd publisher, I started with the Heroine's POV out of habit. I was SO glad you helped me realize that Rock God worked better introducing the hero first. Because though I loved my "Long Walk" homage intro to the heroine, it really worked better for the book to open with Dante rescuing the mysterious homeless woman, THEN revealing the mystery of why she was in that state.

And then that gave my brain the ok to open subsequent books with the heroes' POV because the series revolved around the bands and the fans of the series would want to jump right to the POV of characters they'd already met in previous books, rather than the new-to-the-picture heroines.

This is super helpful. I really appreciate the look at those two books and how their first section/page is generating questions. Thanks so much!